This is a translation of a French language article from “Canard PC”. It was mainly translated by @TheFrenchCritic and copied to pastebin at http://pastebin.com/9YffVPHG. I made some small corrections for grammar and punctuation but basically it’s the same as the original.

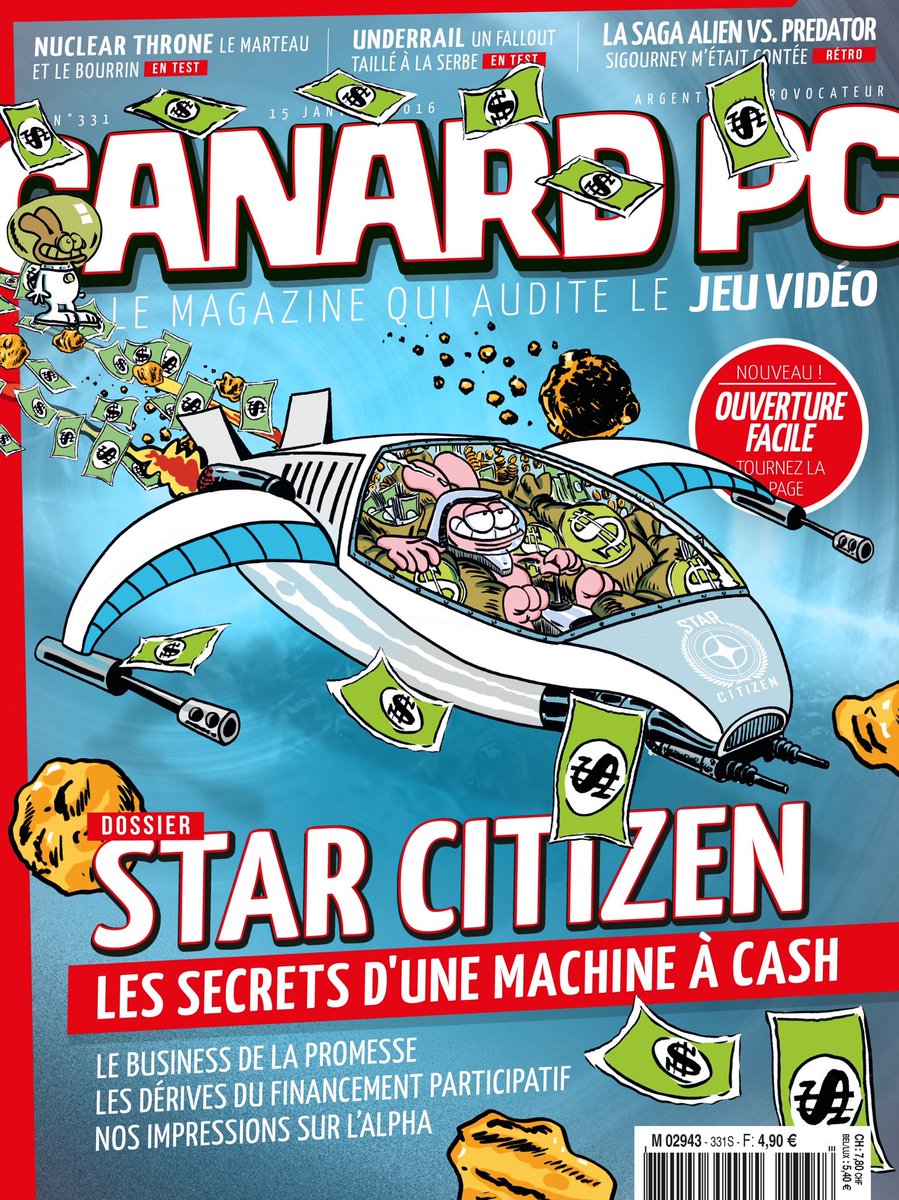

STAR CITIZEN

We came for the money

The story of a guy who needed money to make a game. But as he dug and dug, again and again, he only found gold. So he kept digging.

In December 2015, according to the numbers from its developers, Star Citizen went over the 100 millions dollars mark from crowdincome (yes, I’m mixing the words « income » and « crowdfunding » on purpose, you’ll get why later on). Not only was this amount never seen before (I mean, after getting 40 millions, it went in the Guiness Book as the « highest crowdfunded product, all categories »), but it remains astounding for a PC-only title.

Some videogames are renowned for going over this sum (marketing included), but they tend to be released on all platforms. Only two examples of PC-only games spent that much money : Star Wars The Old Republic, which was a huge disappointment for EA ; and All Points Bulletin, the online GTA-like, an industrial catastrophe that brought its dev (Realtime Games) to bankruptcy. Both used a subscription system to profit from the losses, which officially isn’t what Star Citizen is going for.

The man in charge of spending this enormous fortune isn’t just anyone : his name, Chris Roberts.

The cat-headed man

Chris Roberts, this American who spent his youth in Manchester, barely 20 years old, managed to convince Richard Garriott and his Origin Systems company to start working on Wing Commander, a space simulation fated for a tremendous success in the 90s. But there are many Chris Roberts.

The first one’s a young man who invented the modern space simulation. Unearthed during the Consumer Electronic Show in Chicago during 1990’s summer, Wing Commander’s demo brought panic in LucasArts’ ranks, since they were about to release X-Wing a few weeks later. Their game ended up being postponed for two years as way to catch up. Although David Braben’s Elite had come out as soon as 1984, Wing Commander went much beyond in terms of wireframe models, while marking down what the genre’s gameplay, narration, immersion and feline-faced opponents had to be. That Chris Roberts produced very ambitious and innovative games, extremely popular. He made his fortune from the Wing Commander series, and then by selling his rights to EA when Origin Systems got bought up in 1992.

A second Chris Roberts leaves EA to start Digital Anvil, where he intends to produce games and movies. Wing Commander is the thankfully unique film that comes out. Atrocious burden that Entertainment Weekly graded with a flat zero, accompanied by : “Special effects, rudimentary, are laughable; dialogues are so atrocious, they become hilarious -and they are this movie’s best parts”. In terms of games, the first one (Starlancer, a space fight simulation seemingly interesting but simplistic) is in fact owned by the English studio Warthog. The second one, led personally by Chris Roberts, makes the news for its development trouble. Pushed back numerous times, it comes out in 2003, two years late, with most of the functionalities it had first promised taken away. That Chris Robert disappoints and has a hard time keeping his promises. During the next ten years, he builds a production company in Hollywood (Ascendant Pictures, sold silently in 2010) and is credited as producer of a few films (most notably, Lord of War or The Punisher).

He comes back, pays cash

In 2012, a new Chris Roberts come back to video games like a hero, with an incredible message to gamers : “No, PC gaming is not dead, space simulation either, and with your help I can prove it”. He talks of creating a successor to Wing Commander worthy of this new century, called Star Citizen, and offers a proof video where you can see sequences representative of his goal and a prototype’s progress, made with Crytek’s 3D Cry Engine.

Following, Cloud Imperium Games (the company he started for the occasion) launches, in October of 2012, a crowdfund on the game’s website (robertsspaceindustries.com). The reaction was staggering : the website (a WordPress site with a plug-in for the crowdfund) was broken by the amount of hits for the next days, which pushed them to bring the campaign to Kickstarter as well. Albeit troubled with a server crash, robertsspaceindustries.com announces they reached a million dollars in a week. On Kickstarter, only six days were needed to reach the 500 000 dollars goal. On the 19, November 2012, the crowdfund gathers more than 90 000 donators for an amount of 6,2 million dollars (2,1 of them “only” from Kickstarter). Right away, Star Citizen [becomes] a phenomenon, and no one, not even Chris Roberts, could imagine such a drive and success.

Star Citizen’s dad has been rather varying in the way the project was born and constructed. During its first announcement, he swears the game has been worked on for twelve months with a team of around ten people, and the images shared represent the prototype of their progress. He adds to journalists that the preparation this year cost him a million dollars, gathered by an investors’ pool. Then, he’ll minimize the initial team’s size, turning into “a few people”, sometimes even part-timers. The ever-changing details meet up with the first criticisms, regarding the lack of concrete progress for the game, while advantageously pushing back the “official” release date to start working full-time on it, thus making the delays more relative. That same kind of blur surrounds the projected budget, which is far from trivial.

How much for one Star Citizen ?

If the pilot is to be believed, he first intended, as early as 2010, to come back into gaming, with a title for next-gen consoles (PS4 and Xbox One), eventually under Wing Commander’s name with the help of EA. It’s because of other Kickstarter campaigns’ success, namely Double Fine’s, that he was convinced of testing the challenge directly with the crowd, with the help of investors.

These investors (never named and long since “abandoned”) were, according to him, ready to complete the needed budget for the game, as long as he received at least 2 million dollars in the crowdfund. Chris Roberts aimed for 2 to 4 millions from the crowd, for a total of 10 to 12 millions. Comparing, the initial official budget for Elite Dangerous was 12 million dollars (including 2,5 millions from the Kickstarter), and, says David Braben himself, this “grew up a lot afterwards”. However, Elite Dangerous’ ambitions were much lesser than Star Citizen’s, which promised : a solo campaign à la Wing Commander, with an MMO part that required no subscription, as well as an interaction and global economy system, like in EVE Online, all this gifted to us in 2014, with thanks.

Hoping for all of this to fit in a 12 million dollars envelope, while building a studio from scratch (even though Frontier Developments releases two games per year since 1994), seems much too unrealistic. Later on, Chris Roberts, quite the contradictions spendthrift, successively declare he always wanted to make a game that needed at least 15 million dollars, then the real game required 20 million (once this amount was reached by the backers), but that these 20 millions were comparable to 40 millions from a classic publisher.

The call to donate never stopped, there was no other mention of a provisional cost for Star Citizen, and it became clear the budget was to swell up as fast as the money was to come in. By 65 million dollars, Cloud Imperium Games (CIG) simply ceased adding new mechanics promises. No one can tell what the 100 million dollars they reached at the end of 2015 will be for, since Chris Roberts also assured us that “the entirety of the collected funds before launch will be spent in development to enrich the game’s vision”, and that “the company keeps a solid amount of cash and works prudently in accordance to its monthly income”.

STAR CITIZEN, AN EVOLVING PROJECT

In three years, the game’s definition evolved a lot, as the millions and promised concepts kept piling up.

2012’s promises :

– an epic solo campaign of 30 missions;

– a sandbox mode in a continuing universe with coop;

– a multiplayer mode self-hosted by the player;

2015’s promises :

– an epic solo campaign of 50 missions with famous actors

– a sandbox mode in a continuing universe with coop and PvP

– orbital stations to conquer and manage

– spaceship boarding

– FPS mode in the ships, stations and planets

– 100 inhabited solar systems

– procedural generation of planets

– customization and advanced improvements.

From zero to a hundred in less than three years

Until a certain point, hesitations and contradictions are understandable. No one, indeed, ever was confronted to such an event. Expecting two millions from fans, four in his wildest dreams, Chris Roberts ends up three years later with a hundred million dollars.

A bit like some dude digging in his garden to plant potatoes and get a nicer time, who’d blow an oil well. Two million, four million, six million [TN : shut up 8chan]. At first, he tries dealing with the jet by getting all the pans and bowls to contain the liquid before the source ends; but the first stretch goals for supplementary content are pulverized one after the other. So he buys all of the town’s containers and rents swimming pools all around as reservoirs : ten, twenty, thirty million dollars later, all added mechanics and gameplays are reached without the deposit getting close to end. It’s time to build an actual derrick and pipeline, which is what Chris Roberts did, without taking care much about the landscape, the smell or pollution.

At Gamasutra, Roberts explains : “I’d say one of the reasons we managed to raise so much money is that we kind of “gamified” the support”. Indeed, from the start, the campaign was marked out from the traditional plan of a game with a few physical goods of growing value following the backing’s height. Star Citizen bet everything on virtual objects : how much money you gave was how much value the starting ship had. Thus, the game showcased how powerful “collectationitis” and fetishism were in the buyers’ mind, able to go passionate and spend fortunes for a spaceship fleet entirely virtual.

Objective loot

The fact the crowdfunding campaign never stopped had a tremendous pernicious effect. Instead of concentrating all efforts on the game’s development once the financing was done, the continuous exploitation of gamers’ passion became a constant activity, central part of the studio’s missions. CIG’s teams started proposing more and more ships, more and more expensive. Then paying “enhancements” to allow clients to stay up to date with the latest models. That way, unlike the usual plans of crowdfunding, which saw the fanbase pay once then wait more or less patiently until the game’s release, Star Citizen built a mechanic allowing you to come back to the checkout several times before the game’s release. Quite logically, a true marketing structure was put into place around this, so that the client’s obsession could feel flattered and the studio could get maximized profits. There, new ships but also new promotional video clips are created; under the pretense of getting you immersed into the universe (just like a fake commercial for science-fiction movies), they are genuine promotional ads for indeed virtual yet actually sold products.

The very cycle of the game’s development is called upon : that way, the first available “playable” element isn’t a trip to space to feel how the gameplay goes, but the “hangar” in which players can simply admire their ships so expensively obtained, without ever being able to pilot them. A mere luxurious showroom exposing the machines with a profusion of details and a level of time-consuming finishing that no other development team would accept at such a state in a project.

And it worked. Very, very well, even. By the end of November 2014, Cloud Imperium put up for sale 200 ships (Javelin destroyers) for 2500 dollars each. You read that right, 200 virtual ships for a game that doesn’t exist yet sold for 2500 real dollars. As Wired reported, only a minute was spent before they got sold and brought 500 000 more dollars into their till. Armed with marketing, limited editions, special operations or sales, the new economical model Chris Roberts invented raked in millions every month with an intriguing regularity : 34 more millions during 2015, nearly 3 millions per month, easy.

Who gives what ?

Cloud Imperium obviously doesn’t communicate Star Citizen’s sales details, but everybody knows what’s involving the initial Kickstarter campaign, and its interesting analysis.

To remain coherent, let’s discuss the 31,263 people who gave between 30 dollars (the minimum to get the game) and 500 dollars (eliminating the 27 backings of 1000, 25000, 5000 and 10000 dollars, which we’ll call “eccentric”) for a total of 1 882 732 dollars.

While the average goes to 60 dollars per person, half this population gave 37 dollars or less. This shows that the average isn’t the most reliable gauge. The 15% most cautious clients represent 7,5% of the total sum (30 dollars on average), while the 15% biggest spenders (110 dollars or more) gave 43% of the total (173 dollars on average, or six times more than the cautious, and three times more than the general average).

Whales in space ?

We can add that this “test” population for the Kickstarter was much more “mainstream” and much less filled with passion than the one that gave directly on the site; and that the real numbers and backing gaps are thus much more intent for the entire audience. To verify this hypothesis, we we were able to study the fleet of around 250 French gamers involved enough to get into a guild, and estimated the cost of those ships.

It appears those that remained under the 50 euros mark -standard price for a big PC game- represent a minority : only 23%. More than half (51%) own one or more 100 euros and beyond ships (three times more than on the initial Kickstarter), and are even a third (32%) to go over the 200 euros !

Star Citizen exists then upon a smallish number of huge backers after all, who spend without caution, under an economical model nearing the wildest free-to-play’s, those that wring out a minority of gamers surnamed “whales”. Those gave several thousand dollars (the most surprising public case reaching a hangar of 30000 dollars). Inevitably, like for social games, the question is to know whether it is or not exploiting people with genuine weaknesses.

Who are those nuts in those crazy machines ?

Thing is, we met “invested” Star Citizen players. Not really fanatical, they generally have the same view of the game’s present state : a small content and an annoying tendency from the studio to “add more instead of fixing bugs”, yet a more interesting driving mechanic than in the Elite Dangerous. Moreover, the recurring two words are : want and trust. Want, to see a kid’s dream materialize, the ultimate space game, in a way. While trust, rests obviously on the charisma of Wing Commander and Freelancer’s creator, as well as the crowdfunding system and assumed transparency of CIG. Some kind of opposition to the growing defiance against traditional big publishers. “The trust appeared after the project launched, one of those players explains, when I saw the studio managed to overcome a few issues, like the FPS module’s, to adapt and hire the right people. Today, I feel the development reached its cruising speed.”

Yet, under the surface, caution emerges. About the outrageous marketing by CIG, for example. “When I see people spend small fortunes for scientist or repair ships (not even modelled yet) on the only promise that “doing research or repairing a hundred ships in a row, it’ll be rad”, or that it’s possible to buy credits (around 10 euros for 10000) when we don’t even know what they’ll be used in-game or the price in credits of those ships, I seriously start being questioning this.”

A POPULARITY THAT CAN’T SEEM TO BE QUESTIONED

Delving into Star Citizen’s numbers implies feeling dizzy seeing how high the sums can go. For example, Star Citizen gathered more donations in 2014 (34 million dollars) than all other games on Kickstarter that year (20 million dollars).

A few days before Christmas, the official numbers from Cloud Imperium reached a total of 102 million dollars for around 1,12 million backers. By the end of 2015, the average donation was of 91 dollars (or pretty much the same as a AAA game sold with its season pass, or a collector’s edition with a resin figurine made in China). This average is strangely steadfast : in the initial campaign, November 2012, the average was 70 dollars per person. It lowered a bit for six months (which seemed logical, since the most interested fans had gotten involved early on), but then follows a surprising growth that pushes it to more than 100 dollars by the end of 2013, until it remains relatively stable (very small drop) for two years. It could’ve been expected that the game had reached its audience, and new backers would become rarer then. According to the numbers from Cloud Imperium, there is no such thing, as the arrival of new clients only slightly lowers.

Keep in mind, though, that the official number of “citizens”, is but a reference for how many backers (and thus is useful to calculate the global average backing), is very probably inflated, so much as the number of subscribers during the free trial periods or by gamers who opened several accounts (for example to speculate or enjoy an interesting and limited offer several times). One last thing : all the numbers are given by CIG, with no way to verify. Nothing proves they are genuine.

In space, no one can hear you pray.

Ah, Star Citizen’s marketing… Here again, our gamers show lucidity : one admits he “isn’t proud” of spending 150 euros in the shop. The other estimates himself as “rather unreasonable” with 300 euros in ships. Both started with a basic pledge, and, with each limited offer and commercial (following the ones telling you to let go of your rent to buy the latest Mercedes, and “hugely efficient, I’ll admit”, they say) made the bill raise. Even when they were being hesitant about the project’s continued existence : none of them would swear that Star Citizen would honor all of its promises. A mixture of trust and an act of faith.

Not a surprise considering the most involved players, literally, spent more than average : when you blow hundreds of dollars in ships, some of them still not drivable in the present 2.1 alpha, the last thing you’d like to hear, and even less admit, is that the game to come might turn out bad, broken or worse, not come out. A real self-dense reflex, mixture of how, self-persuasion and even sometimes a bit of resignation, as this gamer shares when, even though he spent as much as three new games, would find himself “satisfied if at least Squadron 42 (the solo campaign) saw the light of day”.

Ship loot

For the outside viewer, that ship store certainly is the wildest element from Star Citizen. Think of it this way : CIG sells virtual ships (a hefty hundred of different models) for prices ranging from twenty to several thousand euros. Everything’s going in there : commercials, limited offers both in time and quantities (yeah, yeah, there’s such a thing as “shock shortage” of virtual items, sure), amelioration of ships you already own… Our outside observer will wonder, understandably, what can push someone to buy, for such amounts, ships in a game that offers a very, very tiny taste of the final product in its present alpha.

If we ignore the smartpants who’ll try to benefit in parallel markets (officially non-approved by the studio, yet only softly fights against this), the answer is : the dream, the wish to support a bit more this project for the idealists. And impatience, too, surely. Since all those wonderful machines will be, CIG promises, purchasable in-game, with the game’s money -not your bank account’s; while we wait for Star Citizen’s release, it’s the only way, for now, to get them and pilot them. In any case, regarding this last part, if they’ve gone beyond mere concept, which isn’t the case for all models. Ah, it seems our outsider is having a stroke…

My financing deep into your gameplay

This frenetic sale of ships, by the way, brings its own load of issues. Or at least questions.

To promise you’ll be able to own, from playing, this Destroyer Javelin sold for 2500 dollars or any other ship presently in shop by starting aboard the Aurora “Space Twingo” MR delivered with the minimal pledge of 30 dollars was unavoidable. It was the engagement not to turn Star Citizen into a pay-to-win, true love-killer in occidental markets for multiplayers.

But the thing is, if acquiring bigger ships, more powerful ones, is a system Chris Roberts’ game will rely upon (it follows the genre’s codes, so it’s easy to assume), starting from the get-go with a huge ship might expose the player to the situation of “sure, and then ?”. Otherwise, if it’s only the start, this implies players starting in so that the ones who spent more than 200 euros don’t feel cheated. A real balancing headache, to which we don’t have an answer… But we’d rather be convinced that Christ Roberts, in his case, had it before he opened his small virtual dealership.

If it’s obviously easy to pressure gamers enthralled by the project, it’s much harder for them to go back and get refunded. According to several accounts, even when using the most honest reason in the world, namely considering that adding new legs to a millipede (and accumulate the delays) makes the game change from what it used to be when you signed in in 2012, you’ll face a polite, but stern refusal from the studio. In fact, it seems much easier to get a refund when you don’t ask for it, like it happened to Mr. Derek Smart.

Dédé’s crusade

Ah, you didn’t think we’d forget about this dear Derek Smart, did you ? To those who never heard of him, this American developer had backed Star Citizen with 250 dollars and saw, in a way, his membership card taken away from him and his money refunded after CIG got annoyed at him

1) officiously : for hating on the game, its development and Christ Roberts in a torrent of varied accusations;

2) officially : for using Star Citizen’s forums to make himself known and promote his own game.

Derek Smart, CEO of the 3000AD studio, indeed has improvised himself leader of an anti-Star Citizen rebellion. Over time, the situation never stopped getting worse. With objective criticism (trampled time limits, refund conditions, doubts about the project and its financing…) [allegations from] anonymous previous employees (who, as anybody would know, are [obviously] an objective and unbiased source) and grave accusations, from racism in management to embezzlement. And even ad hominem attacks, like the time he met with Sandi Gardiner, then vice-president of the marketing department of CIG, married to Chris Roberts, to whom the dear Derek sent words that lacked no suspicion of incompetence or string-pulling, or a good ol’ stench of misogyny. Indeed, a good little crusade that quickly took turns to personal warring, where respectable arguments disappeared into a layer of bad faith and toxicity, yet received quite a lot of attention.

The site The Escapist, notably, relayed Derek Smart’s “info”, triggering CIG CEO [Chris Roberts]’s anger, who in turn threatened to sue for defamation. Fun times. Meanwhile, Derek Smart got himself a reputation. Yet not a model one : his last game, Line of Defense, is an MMO shooter in early access [which is] of rare mediocrity, for which the dear Derek Smart sells weapon packs reaching 65 euros. Quite relative moral lessons and game design of this self-proclaimed “defender of developers and protector of gamers’ rights”.

TECHNOLOGICAL ASIDES

A press release from last summer made many observers emotional : the announcement that Frankfurt’s team had spent eight months on the 3D engine’s conversion to a precision of coordinates to 64 bits [Translator’s note : not an expert on the terminology, might be wrong here and in the following descriptions]. Obscure for the uninitiated, this decision might be heavy with consequences, not only for all the work it needed beforehand, but also for future performances.

To comprehend this better, we asked three French professionals with a lot of experience about it : a project leader working inside the American superpower; an ancient AAA game producer at a very big publisher; and the director of the 3D engine of a world-famous studio (they preferred remaining anonymous to cause no harm to each of their employers).

“The issue with a space game, the project leader explains, is that distances we deal with are ginormous, and thus 32 bits coordinates are quickly useless. Also, since they need huge values, you lose precision.” Thus, he [Derek Smart] perfectly understands the point of a 64 bits precision, but “the issue is the video card, which still only supports 32 bit. So you have to go into 64 bits to deal with that issue.” According to him, the conversion implies you must rework all shaders, all rendering process, to balance between buffers and performances : “Do this at the very end is like building a house and then digging the foundations”, he contends.

Our second interlocutor, the producer now at the head of a studio, approves and is astonished in a more polite way : “It is surprising, and means they came in very late to a complete situation of the game. I think my technical director would have been alarmed from the project’s start…” To Star Citizen’s defense, it’s rare this type of big production on several years won’t meet a difficulty needed an important readjustment. Thus, our technical director, while sharing the other ones’ skepticism, assures with a smile he sometimes had to modify elements two months before his game’s release “that were so massive they would have been laughed at by everyone had anybody heard”.

All three agree it is worrying so many elements related to the gameplay from the start added up.

Reasons for doubt

You see, Derek Smart is a self-centered man hoping for notoriety whose defamatory eruptions reach burlesque levels. Yet, not only true nutcases are worried by the unending development of Star Citizen, which has so far neither clear budget nor official release date.

We reminded you a year ago of the structural causes of worry, especially the difficulty to develop a project of this size by a studio created from nothing with more than 250 people in four different regions (Los Angeles and Austin in United States, Manchester and Frankfurt in Europe). The accumulation of announced mechanics for two years would make anyone fear that Star Citizen lacks a vision, having been changed many times.

Technically speaking, the game seems to want to accumulate the wrong challenges. For example, picking the CryEngine, made with FPS in mind, to deal with a space fighting game involving heavily complex 3D models, dozens of meters in length, requires serious changes. Adding to it, during the development, an FPS fight module, is in itself a surprising choice regarding the main gameplay; but going for a revamp of the entire animation system in CryEngine (albeit ready for it) seems to follow a strange perfectionism, even if you find for it the perfect architect for that animation system itself.

Chris Roberts is certainly surrounded by competent people, and his own brother Erin is a game producer with a lot of experience, but many accounts indicate he gets too involved in the title’s details even though he hasn’t produced anything in a decade. Something that will reassure no one : remember that Chris Roberts’ last game production (Freelancer), the deal turned to a fiasco because of the excessive ambition. After years of delay, Microsoft got impatient and bought the studio nearing bankruptcy (Digital Anvil, 2000), sold what was being worked on, fired Roberts while keeping him as a consultant and finalized Freelancer by cutting swiftly in the unrealistic promises it had made.

It seems indeed today that this excessive perfectionism caused by an unlimited budget brought Chris Roberts to raise the difficulty of a production already extremely complex. He seems to have been a bit random about his game’s definition, and, while he boasted about being able to make it for less than a big publisher, he loses time (and thus, money) when remaking entire parts of his engine, and collects delays. Just like our 3D engine expert told us, used to ambitious and years-long productions : “Is the game feasible ? Probably. By them ? I couldn’t say.”

THE BEST AND WORST OF CROWDFUNDING

Star Citizen makes promises a business : clients give because they trust; the more they give, the more they turn into fervent fans of the game (otherwise, they would have to admit they were had, which explains some exaggerated reactions from backers to any criticism on all forums in the world). This self-entertained ability is a formidable drive for the game, which explains partly its success.

But this faces in the same vein a huge risk of backlash : if trust starts falling, it’s an avalanche of generous donators, humiliated, turning into animals cutting the legs of developers and making buyers run away. The worst thing of it all is that the more waiting and hope gather, the more disappointment will be the only result and the game’s release a risk.

It’s likely, seeing the way it’s marketed and developed, that Star Citizen will remain for years in the works, accumulation of small and big pieces, never really full and always perfectible.

WE WOULD HAVE LIKED TO KNOW…

We obviously contacted Cloud Imperium Games to have a few precise answers to some questions. Like, knowing, for example, the official budget for Star Citizen, hearing the reasons and potential impact of the coordinates system’s change in their engine, or know if creating new ships was going to last for a bit longer. Alas, even with our hardest attempts (during times where year-end holidays make transatlantic communications sometimes arduous), we left with but a small booty :

yes, the solo mode Squadron 42 is planned for 2016;

no, Star Citizen doesn’t have a release date.

One thought on “Criticism of Star Citizen–from “Canard PC””